The Story Behind the Picture, a Conversation with a Player Who Was There

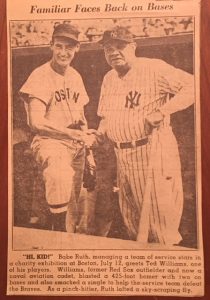

Seventy-five years ago, two of the world’s greatest hitters met in person for the first time at Fenway Park when the U.S. Navy granted Ted Williams leave to play on an armed forces team managed by Babe Ruth. The Fenway Park exhibition, where Ruth’s “All-Stars” faced Casey Stengel’s Boston Braves, was arranged to purchase eye glasses, leg braces and artificial limbs for war victims along with milk and food benefiting underprivileged kids.

“Hi Kid!” Sporting News clipping with Ted and Babe at the July 12, 1943, charity exhibition at Fenway.

Other military stars on Babe’s team included former Boston Red Sox “Dom” DiMaggio, a naval trainee, as well as 95-year-old George Yankowski, a former catcher with the Philadelphia Athletics who became an Army sniper and helped win the Battle of the Bulge.

Yankowski stood behind the photographer when the iconic homecoming photograph was taken in front of the Red Sox dugout. He said it was a “hot … hot humid day” with reporters and photographers hovering around Williams and Ruth like “ants on honey.” Yankowski recalled that Ruth was “drinking cold beer out of white pitcher.” That day Yankowski wore his woolen Fort Devens jersey and Williams returned to Fenway in his 1942 Red Sox traveling uniform, baggy from months of intense physical training as a Navy cadet. According to recent discoveries, the Bambino is dressed in a pin-striped Yankees uniform made by Western Costume Company for his role in “The Pride of the Yankees,” which is currently displayed at the National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum exhibit, Babe Ruth: His Life and Legend.

As Williams beams with an exultant smile, another behind-the-scenes story unfolds—most revealing of his humble character.

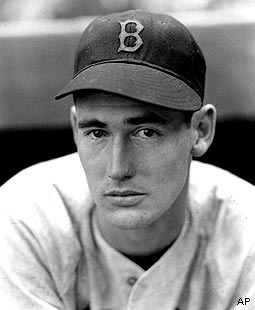

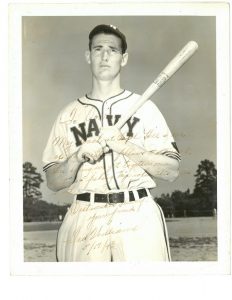

In mid-1943, war raged in the Pacific where Navy fighters gained the advantage over the Japanese in the skies. That summer, the 24-year-old slugger was spending three months on a North Carolina Pre-Flight Naval Aviation training base, drilling alongside his good friend and Red Sox shortstop, Johnny Pesky. In a Southern heat wave, cadets slogged through the most difficult ground training program in the world for pilots—tackling feats the best athletes would struggle to complete today.

Like Pesky, Williams’s second job at Pre-Flight School was to play baseball on command and though he was exhausted, and bug-bitten from hikes, and stressed from long hours of studying, he never disappointed the crowds—especially the kids.

During the war most fans assumed that players like Williams yearned for the limelight. While the military was careful to limit appearances of celebrity athletes, the Red Sox slugger insisted on being treated like every other cadet in a dog tag, shunning perks and special attention. When the All-Star invitation to Boston arrived, Williams initially expressed a desire to remain on base to focus on his work, proving that his passion for flying equaled his aspiration to become the greatest hitter who ever lived.

When Williams came home to Fenway the media blitz was tremendous. In sweltering humidity, he swaggered up to the plate before a youthful crowd of 18,000 fans and knocked the hide off the ball. That day Williams smacked three home runs in a pregame contest against Ruth, with 20-year-old Yankowski, crouched behind the plate as the catcher. Then the Splendid Splinter belted a tie-breaking homer ten rows deep into the center-field stands in the exhibition game where Babe’s team beat the Braves, 9–8. When the former Philadelphia Athletic catcher got a single at that game, (which knocked in the winning run) Ruth put his arm around Yankowski, and in a husky voice, he said, “Nice going Kid.” When we spoke by phone this week, Yankowski said, “I’ll never forget his words if I live to be 100, which I very well may.”

In the color Fenway Park image carried over the wires, Sporting News, and military publications around the world Williams is tanned and in the best shape of his life, shaking hands with a declining Ruth, who leans on a bat. With packed stands in the background, and music furnished by the U.S. Coast Guard and Army bands, Williams realized that he would soon return to rigors of training. He did not know if he would live through the war or step foot in another major-league ballpark. But for a moment he was home.

During WWII, ninety percent of baseball’s professional players put their careers on hold to serve Uncle Sam—driving tanks, flying airplanes, and fighting the war in many other useful capacities to win the biggest game of all. Less than 45 major-league WWII vets remain with us today, including Cambridge native, George Yankowski, who resides in Florida, where a Bronze Star, a Combat Infantry Badge and the French Legion of Honor award are framed on his hallway of fame.

Ted Williams, who would celebrate his 100th birthday on August 30, 2018, came to symbolize America’s ultimate major-leaguer and Marine Corps fighter pilot serving in both WWII and Korea. Baseball fans will forever speculate what further heights Williams may have achieved in his baseball career had he not stepped off the diamond to serve his country. But perhaps it was Williams’s voluntary absence from the game, his tireless work ethic, and his ability to step back up to the plate as a humble naval cadet, performing as if he had never left Fenway Park, that truly defined Williams’s legacy of greatness.

Anne R. Keene is the author of The Cloudbuster Nine, The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII. Dozens of major-league baseball players trained and coached at these special Pre-Flight Naval Aviation Training Schools along with George H. W. Bush, Gerald Ford, John Glenn and “Bear” Bryant and other members of the Greatest Generation. Today, less than 45 major-league World War II veterans remain with us, representing a generation of players who paused their baseball careers to serve their country.