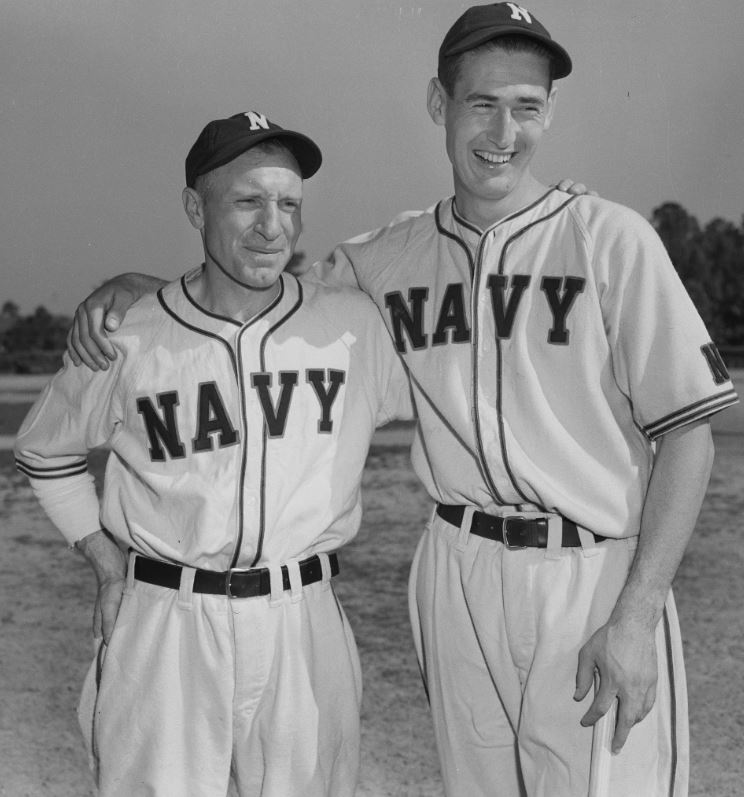

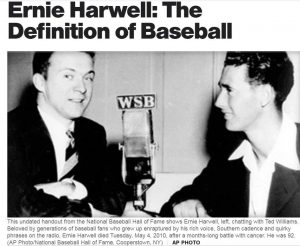

Broadcaster Ernie Harwell visits with Ted Williams: The Definition of Baseball. Courtsey National Baseball Hall of Fame Library and Archives.

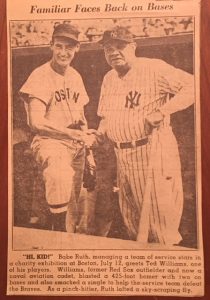

“It’s hard to beat a person who never gives up.” – Babe Herman Ruth.

In a world disrupted by hurricanes, recessions, politics and war, baseball is the constant that gives us heroes. Every fall, the World Series connects the generations. Fathers and sons come together; neighbors unite; strangers root for the same team as millions partake in the tradition that defines America.

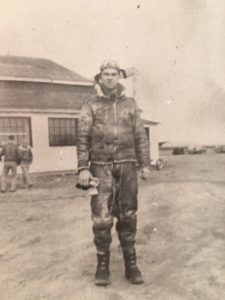

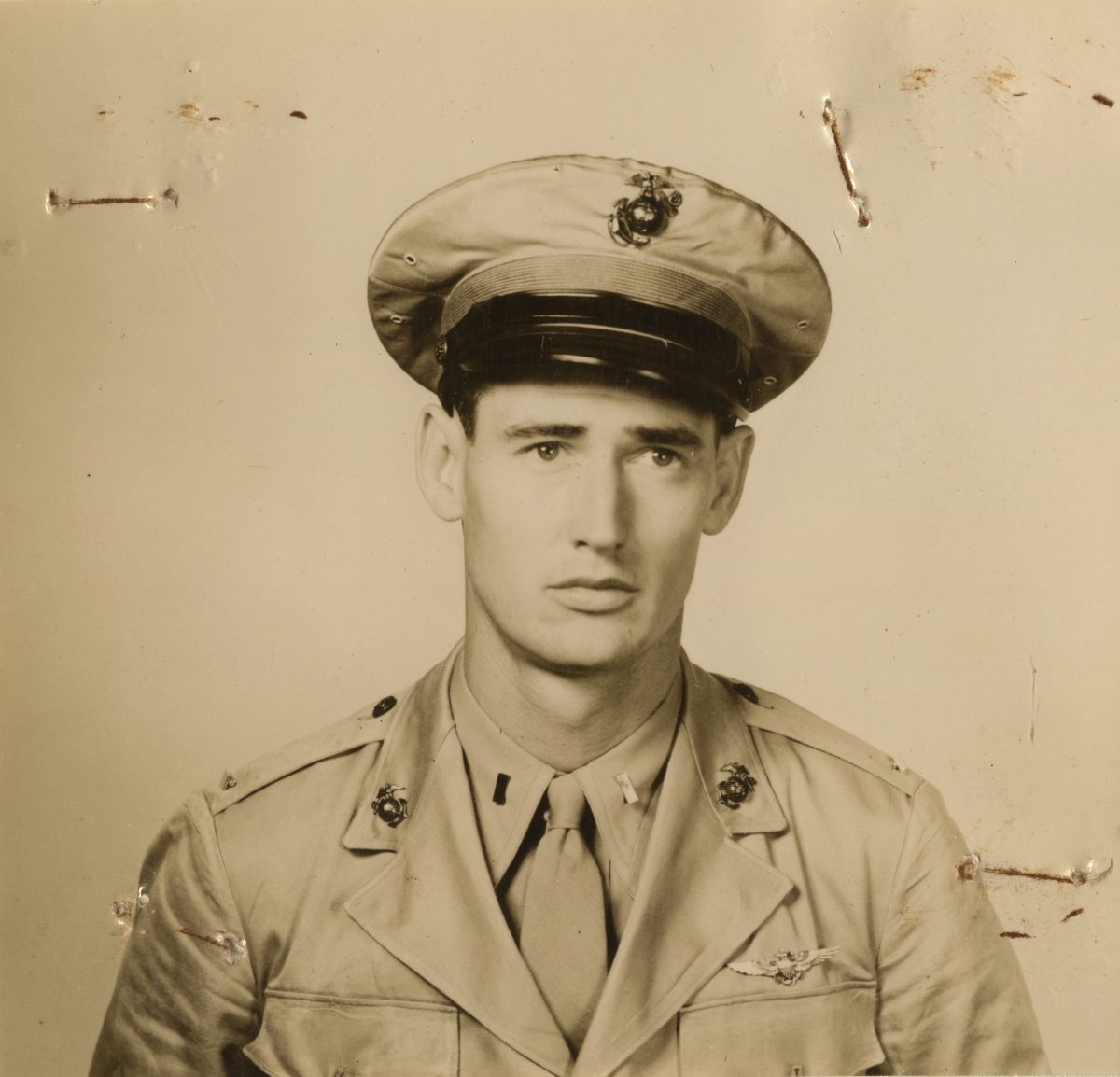

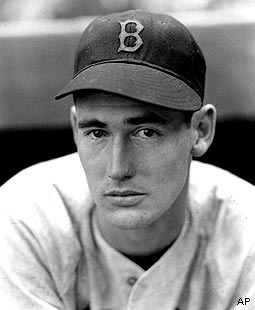

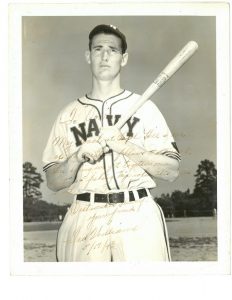

In a world starved for heroes, baseball’s Fall ritual reminds us of players like Ted Williams, the greatest hitter who ever lived who fought in two wars as a Marine combat pilot. We remember miracles, like the “shot heard round the world” when Bill Mazeroski won the championship in 1960 with one swing of the bat. During this year’s Series, we hold our breath, spellbound by the raw and fearless talent of players like Mookie Betts and J.D. Martinez as they go to bat for the Boston Red Sox.

In a world that loves storytellers, one of the game’s most beloved muses was Ernie Harwell, the Hall of Fame Major League Baseball sportscaster who enraptured generations of fans with the saga of our past time. In this 1981 induction (SPEECH LINK) delivered on the porch of the Hall of Fame Ernie tells us what we love about baseball in a world where our diamond heroes help us battle hurricanes, recessions, politics and war. Here are a few of Harwell’s classic lines to remember during the 2018 World Series:

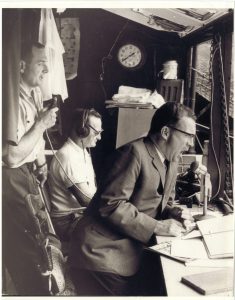

Courtesy, The Ernie Harwell Sports Collection, Detroit Public Library.

“Baseball is the president tossing out the first ball of the season and a scrubby schoolboy playing catch with his dad on a Mississippi farm. A tall, thin old man waving a scorecard from the corner of his dugout. That’s baseball.”

“Baseball is cigar smoke, hot roasted peanuts, The Sporting News, ladies day, ‘Down in front,’ ‘Take Me Out to the Ball Game,’ and ‘The Star-Spangled Banner.’”

“In baseball democracy shines its clearest. The only race that matters is the race to the bag. The creed is the rulebook. Color merely something to distinguish one team’s uniform from another.”

“Baseball is just a game, as simple as a ball and bat, yet as complex as the American spirit it symbolizes. A sport, a business and sometimes almost even a religion.”

“Why the fairy tale of Willie Mays making a brilliant World Series catch, and then dashing off to play stickball in the street with his teenage pals. That’s baseball. So is the husky voice of a doomed Lou Gehrig saying, ‘I consider myself the luckiest man on the face of this earth.’”

“Baseball is a tongue-tied kid from Georgia growing up to be an announcer and praising the Lord for showing him the way to Cooperstown. This is a game for America. Still a game for America, this baseball! Thank you.”

Anne R. Keene is the author of the narrative about a major-league Navy fighter pilot baseball team, The Cloudbuster Nine: The Untold Story of Ted Williams and the Baseball Team That Helped Win WWII.