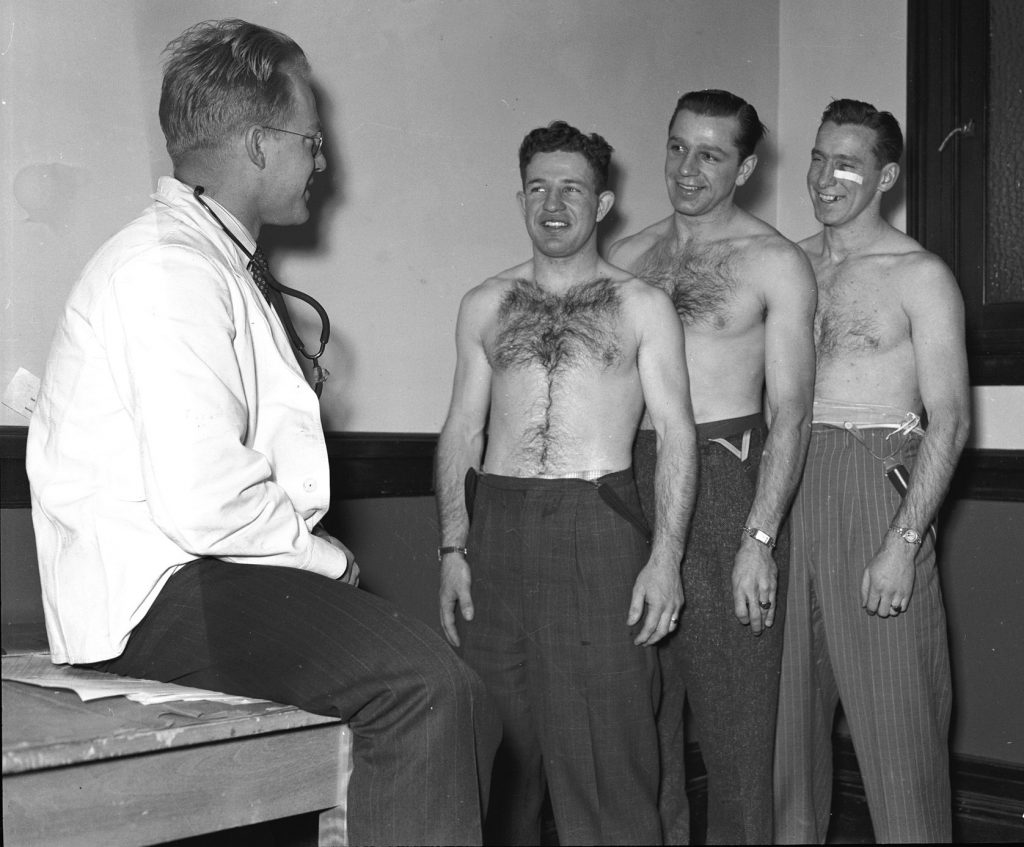

At the height of their success, the Kraut Line for the Boston Bruins was off to war. North America had stayed out of the conflict for the most part, but when Japan bombed Pearl Harbor the future was set. Milt Schmidt, Woody Dumart, and Bobby Bauer had previously joined the Royal Canadian Air Force and it was time for deployment.

Photo by DND Archives

When the time came to go to war, the trio of friends were concerned about their German heritage and how it would be perceived by the other troops. Schmidt asked his mother’s permission to change his last name from Schmidt to Smith. His mother gave permission but ultimately Schmidt thought better of it. Speaking with Jeff Blair of Sportsnet in 2014, Milt said, “To heck with it. What was good enough for my mother and dad is good enough for me.” It turned out to be a moot point, as well. The troops knew quite well who he was and were more than happy to have him with them.

Hockey During the War

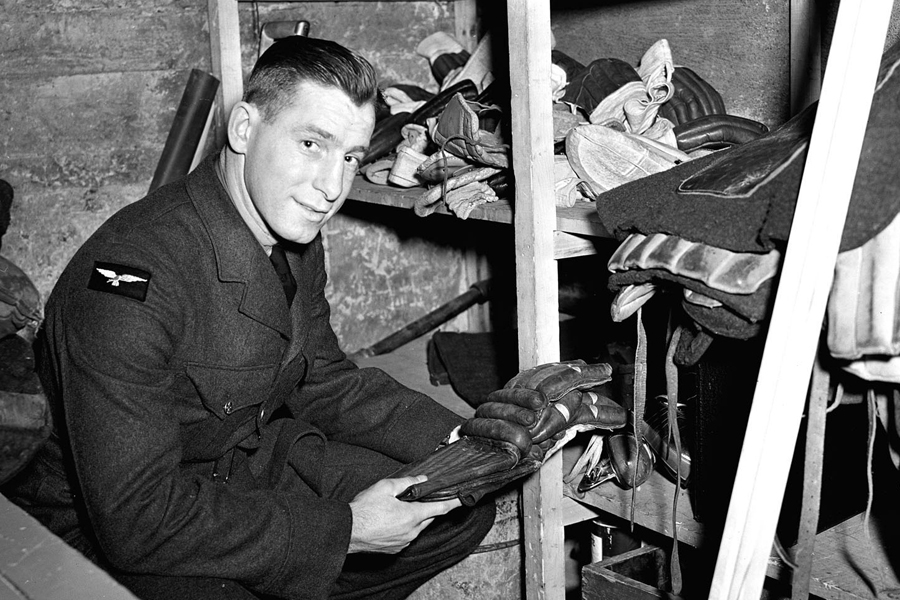

During World War II Dumart and Schmidt were stationed in northern England. They were there for three years and, despite the war, couldn’t leave hockey on hold. Since they couldn’t play in the NHL, they joined the RCAF League consisting of 12 teams. Milt Schmidt and Woody Dumart played for opposing teams, and Dumart’s won the Championship. The following season, however, revenge would be had when Bobby Bauer arrived in England and was assigned to Schmidt’s team. They beat Dumart’s team and won the Championship in 1944. Perfectly summing up the talent of the trio of The Kraut Line, even when separated, they each won a hockey championship in consecutive seasons.

Photo by DND Archives

In 1945 it was finally time to come home. Milt Schmidt later recalled, “Bob went home first. I remember that. Woody and I ended up on the same boat home. Actually, he was going to be going home before I did because I was going to be assigned to another post in the east. I’m not sure I ever knew where that post was. But then good ol’ Harry (Truman) saved me. He dropped the bomb and that ended it.”

Returning Home and to the Bruins

Upon their return home, the Kraut Line reunited with the Boston Bruins for the 1946 season. They hadn’t missed a beat, they were on form and dominating games. And they returned to a bit of controversy as well. Not wanting to be considered politically incorrect after the war, the Bruins held a contest to rename “The Kraut Line”. The winning nickname was “The Buddy Line”. The fans never took the new name seriously, and it only lasted about a month before “The Kraut Line” was permanently reattached to the trio.

While they returned to form and played their always fierce and intense game, Schmidt, Bauer, and Dumont wouldn’t win another Stanley Cup as players (though Schmidt would win two more in 1970 and ’72 as Bruins General Manager). Bobby Bauer won the Lady Byng again in 1947, and Schmidt won the Hart Trophy for MVP in 1951.

The End of an Era

The Kraut Line officially ended with Bauer’s retirement in 1947. Dumart retired in 1954, and Schmidt retired part-way through the following season to take over as the Bruins head coach. All three of them played their entire careers for the Boston Bruins. After his retirement, Bobby Bauer went back to Kitchener, Ontario, where he coached several amateur hockey teams. He died of a heart attack in 1964, at the age of 49. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1996.

Woodrow Wilson Clarence “Woody” Dumart remained in Boston, where he worked as the official scorer at Boston Garden, as well as being the coach of the Bruins’ Alumni Association Team. He died from heart failure in 2001 at age 84. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1992.

Milt Schmidt went from star Bruins player to Bruins Head Coach for 11 seasons before becoming General Manager. He won a total of four Stanley Cups, all with the Bruins organization. In 1980 Schmidt’s #15 jersey was retired, and to this day he’s known as “The Ultimate Bruin”. Schmidt died of a stroke in 2017 at the age of 98. He was inducted into the Hockey Hall of Fame in 1961. The Kraut Line is arguably the greatest line in the history of hockey. But they’re more than just a catchy name. These were men of honor. They had a sense of pride and a sense of duty. And they were better at hockey than everyone else.

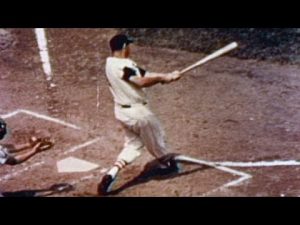

Photo courtesy of Getty Images